Asynchronous Operations: Introduction

Asynchronous operations allow cooperative multi-tasking. Code that utilizes the async infrastructure can hide I/O latency and data fetching. So, if we have code that has operations that involve some sort of waiting (e.g., network access or database queries), async minimizes the downtime our program has to be stalled because of it as the program will go do other things, most likely other I/O somewhere else.

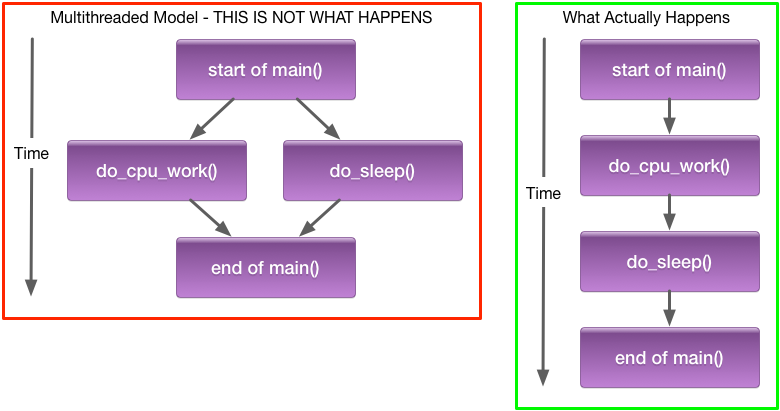

Async is not multithreading---HHVM still executes a program's code in one main request thread—but other operations (e.g., MySQL queries) can now execute without taking up time in that thread that code could be using for other purposes.

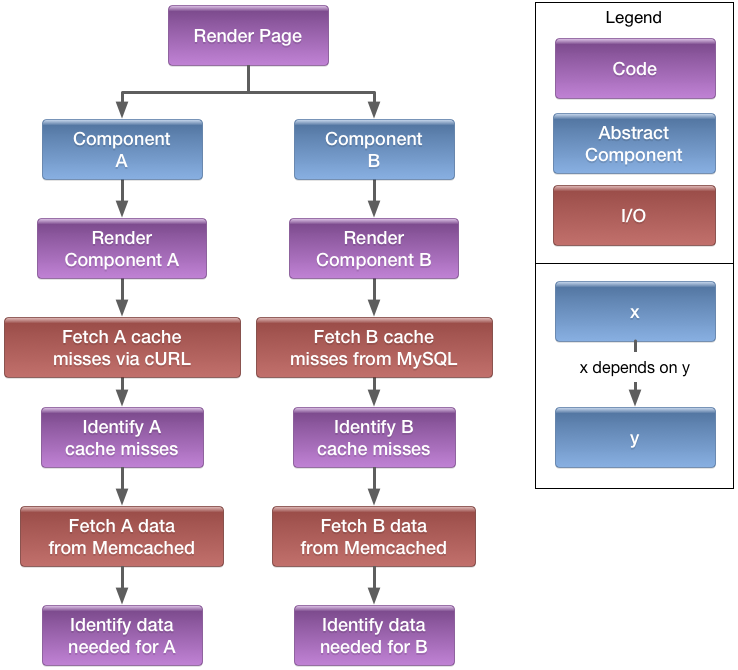

A Page as A Dependency Tree

Imagine we have a page that contains two components: one stores data in MySQL, the other fetches from an API via cURL. Both cache results in Memcached. The dependencies could be modeled like this:

Code structured like this gets the most benefit from async.

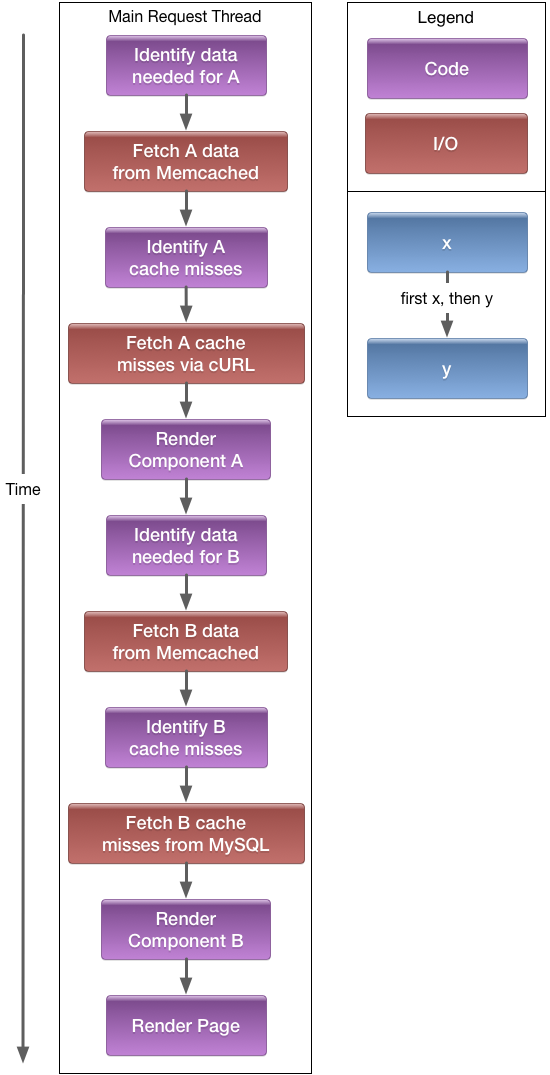

Synchronous/Blocking IO: Sequential Execution

If we do not use asynchronous programming, each step will be executed one-after-the-other:

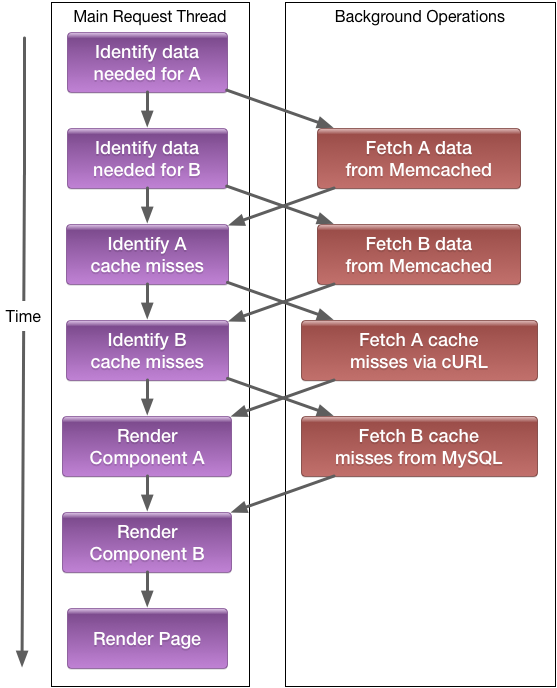

Asynchronous Execution

All code executes in the main request thread, but I/O does not block it, and multiple I/O or other async tasks can execute concurrently. If code is constructed as a dependency tree and uses async I/O, this will lead to various parts of the code transparently interleaving instead of blocking each other:

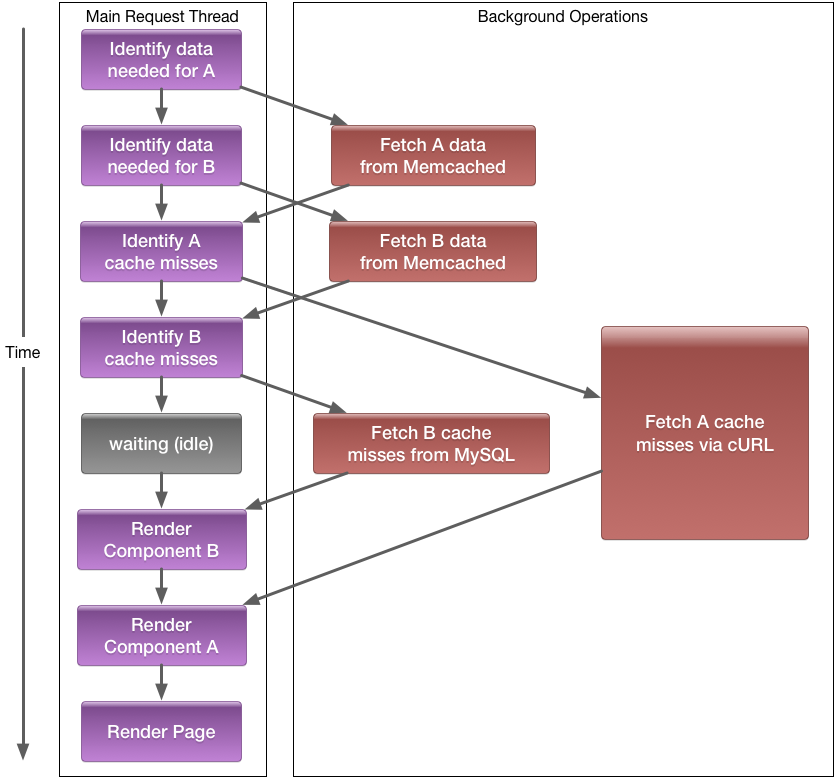

Importantly, the order in which code executes is not guaranteed; for example, if the cURL request for Component A is slow, execution of the same code could look more like this:

The reordering of different task instructions in this way allow us to hide I/O latency. So, while one task is currently sitting at an I/O instruction (e.g., waiting for data), another task's instruction, with hopefully less latency, can execute in the meantime.

Limitations

The two most important limitations are:

- All code executes in the main request thread

- Blocking APIs (e.g.,

mysql_query()andsleep()) do not get automatically converted to async functions; this would be unsafe as it could change the execution order of unrelated code that might not be designed for that possibility.

For example, given the following code:

use namespace HH\Lib\Vec;

async function do_cpu_work(): Awaitable<void> {

print("Start CPU work\n");

$a = 0;

$b = 1;

$list = vec[$a, $b];

for ($i = 0; $i < 1000; ++$i) {

$c = $a + $b;

$list[] = $c;

$a = $b;

$b = $c;

}

print("End CPU work\n");

}

async function do_sleep(): Awaitable<void> {

print("Start sleep\n");

\sleep(1);

print("End sleep\n");

}

async function run(): Awaitable<void> {

print("Start of main()\n");

await Vec\from_async(vec[do_cpu_work(), do_sleep()]);

print("End of main()\n");

}

<<__EntryPoint>>

function main(): void {

\HH\Asio\join(run());

}

New users often think of async as multithreading, so expect do_cpu_work() and do_sleep() to execute in parallel; however, this will not

happen because there are no operations that can be moved to the background:

do_cpu_work()only contains code with no builtins, so executes in, and blocks, the main request thread- While

do_sleep()does call a builtin, it is not an async builtin; so, it also must block the main request thread

Async In Practice: cURL

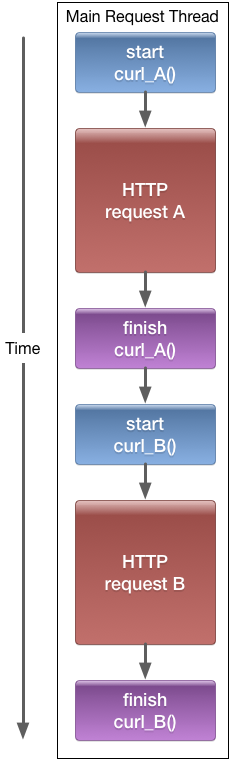

A naive way to make two cURL requests without async could look like this:

function curl_A(): mixed {

$ch = \curl_init();

\curl_setopt($ch, \CURLOPT_URL, "http://example.com/");

\curl_setopt($ch, \CURLOPT_RETURNTRANSFER, 1);

return \curl_exec($ch);

}

function curl_B(): mixed {

$ch = \curl_init();

\curl_setopt($ch, \CURLOPT_URL, "http://example.net/");

\curl_setopt($ch, \CURLOPT_RETURNTRANSFER, 1);

return \curl_exec($ch);

}

<<__EntryPoint>>

function main(): void {

$start = \microtime(true);

$a = curl_A();

$b = curl_B();

$end = \microtime(true);

echo "Total time taken: ".\strval($end - $start)." seconds\n";

}

In the example above, the call to curl_exec in curl_A is blocking any other processing. Thus, even though curl_B is an independent call

from curl_A, it has to sit around waiting for curl_A to finish before beginning its execution:

Fortunately, HHVM provides an async version of curl_exec:

use namespace HH\Lib\Vec;

async function curl_A(): Awaitable<string> {

$x = await \HH\Asio\curl_exec("http://example.com/");

return $x;

}

async function curl_B(): Awaitable<string> {

$y = await \HH\Asio\curl_exec("http://example.net/");

return $y;

}

async function async_curl(): Awaitable<void> {

$start = \microtime(true);

list($a, $b) = await Vec\from_async(vec[curl_A(), curl_B()]);

$end = \microtime(true);

echo "Total time taken: ".\strval($end - $start)." seconds\n";

}

<<__EntryPoint>>

function main(): void {

\HH\Asio\join(async_curl());

}

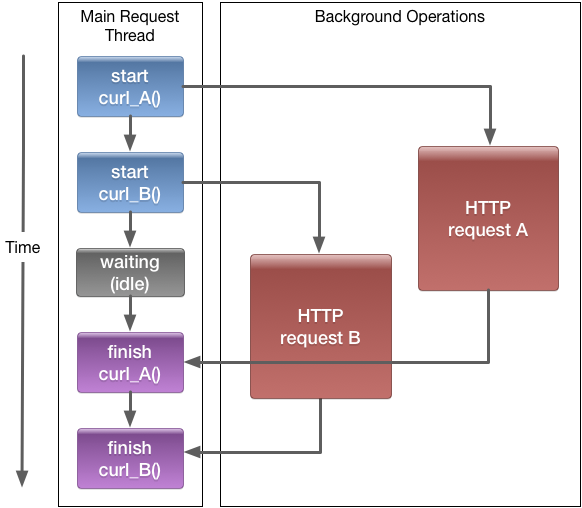

The async version allows the scheduler to run other code while waiting for a response from cURL. The most likely behavior is that as we're

also awaiting a call to curl_B, the scheduler will choose to call it, which in turn starts another async call to curl_exec. As HTTP requests

are generally slow, the main thread will then be idle until one of the requests completes:

This execution order is the most likely, but not guaranteed; for example, if the curl_B request is much faster than the curl_A HTTP request,

curl_B may complete before curl_A.

The amount that async speeds up this example can vary greatly (e.g., depending on network conditions and DNS caching), but can be significant.